Biometrics and deepfakes: tracking uniqueness

We live in historically crucial times, technology-wise. Every week, new laws and regulations aimed at mitigating the risks of AI are proposed and discussed by dedicated teams from governments and coalitions all over the world.

The goal is to ensure the safety and transparency of these complex systems, along with demanding accountability for providers/manufacturers. As we write, three important elements are converging on the European scene, providing a great window of opportunity:

- the debate on foundation models in the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act);

- the regulatory vacuum and lack of safeguards around deepfakes;

- the imminent conclusion of the trilogues on the AI Act, set for December 2023.

Can the AI Act be finalised in time to protect fundamental rights (as European regulation is praised for doing), while tackling the issue of deepfakes proliferation? The answer is yes, it sure can! It is the author’s belief that, in order to solve the problem, the AI Act should target the very root of the technology with which deepfakes are created.

What are foundation models?

An emerging type of AI system is a ‘foundation model’, sometimes called a ‘general-purpose AI’ or ‘GPAI’ system. These are capable of a range of general tasks (such as text summary, image manipulation and audio generation). Notable examples are OpenAI’s GPT-3 and GPT-4, foundation models that underpin the conversational chat agent ChatGPT.

via Explainer: What is a foundation model? Ada Lovelace Institute.

Foundation models that generate images resembling individuals pose two critical challenges: they rely on vast amounts of personal biometric data, often without consent, and require biometric details to produce realistic representations.

The proliferation of affordable computational resources has democratized the creation of deepfakes, making it almost a mainstream practice, and blurring the lines between reality and fabrication.

The corporate world tries to answer

Big-tech corporations tend to portray certain technological “advancements” as inevitable and necessary, while claiming to be responsible enough to handle such major changes. This is evident in statements such as Microsoft’s responsible use of AI during the elections :

Microsoft will help candidates and campaigns retain greater control over their content and digital personas by launching Content Credentials as a Service (CCaaS). This new tool enables users to digitally sign and authenticate media using the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity’s (C2PA) digital watermarking credentials, a set of metadata that encode details about the content’s provenance using cryptography.

Let’s break down this statement and scrape off the corporate jargon. The statements means that

- only Microsoft can issue a certificate of trustworthiness;

- if there is no such certificate, you should assume that the content is fake.

And this assumes that:

- fake content can be generated thanks to Microsoft technology, so they can’t avoid it;

- Users have to go through the trouble of getting a certificate because Microsoft technology has made the Internet less reliable.

AI Act regulators should not buy this narrative

We should reflect on the strong links between:

- The massive GDPR/biometric personal data violation happening when a foundamental model is trained;

- the co-dependence between biometric profiling and deepfake creation.

This reflection naturally takes into account that the genie is out of the bottle, and malicious actors will still manage to produce fakes, This is known and cannot be hindered by watermarking, detection, or prohibition.

So far, none can help the detection, despite what Google says

🤔

What we can aspire to is to address ethical and practical issues related to safeguarding our identity. Two areas in particular, facial biometric recognition and deepfakes, are becoming increasingly prominent in the public debate. But why are these two domains particularly concerning? The answer lies at the heart of human uniqueness.

Facial biometric recognition is not limited to recognizing an individual’s physical features; rather, it deals with a category of particularly sensitive data. Like genetic codes, the features of our faces are immutable. It’s not merely an image or temporary information, but the very essence of our individuality. Once acquired and recorded, these data become a permanent tracker. Unlike computer cookies, which can be deleted, or phone numbers, which can be changed, our faces and DNA remain unaltered.

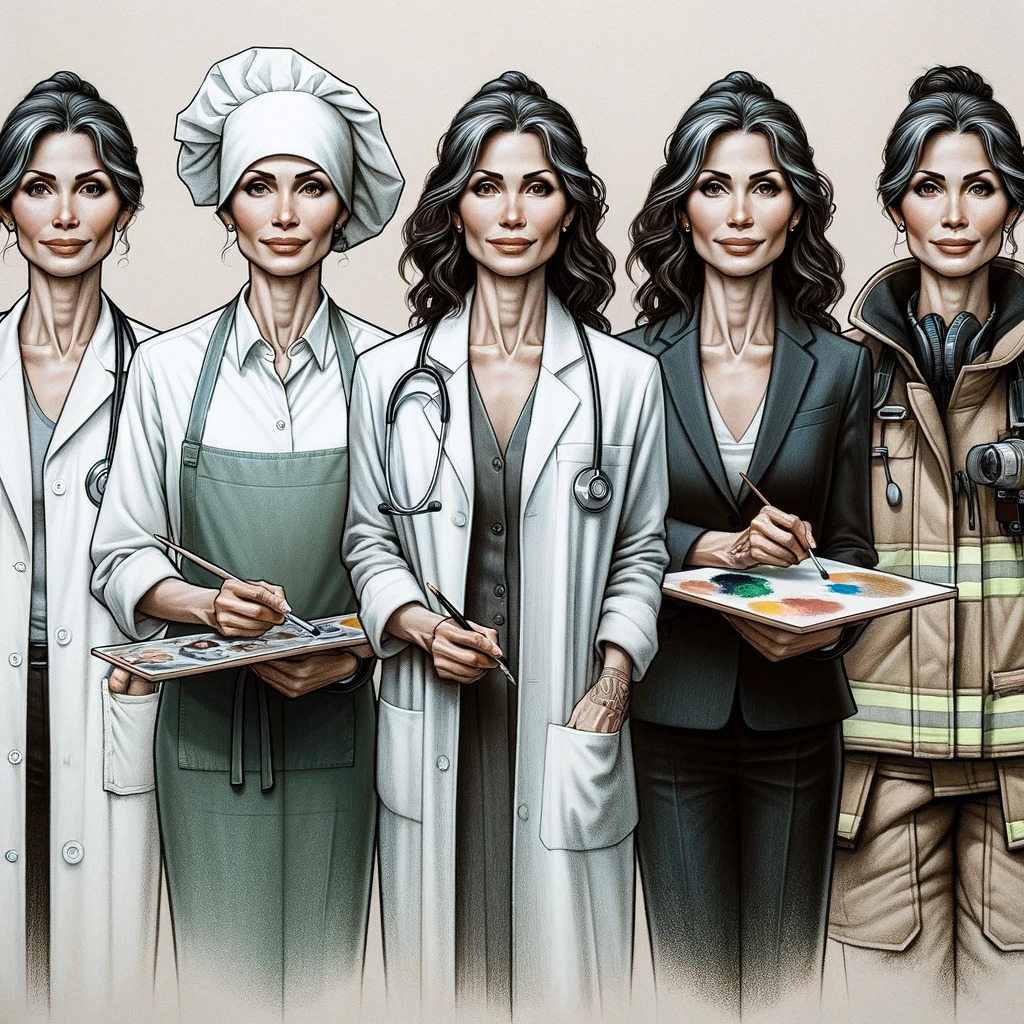

Conceptual illustration of a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) in action. The scene shows two different anthropomorphised machines, one of which is about to replicate the other.

This is why it is imperative to approach the issue with extreme attention to the foundational elements. Technologies that extract identifying points from faces have a lot in common with those used to produce fake images or videos, the so-called deepfakes. The adoption of technologies that process biometric data should not be taken lightly as it is based on the dissemination of models that can be used to infringe rights more than to protect them.

A central element in the production of deepfakes is called “the discriminator," 🤔 which is a component of Artificial Intelligence responsible for verifying the “quality” of the generated images, discerning whether the AI’s chosen path is the most effective in producing a fake or if it needs to explore others. To perform this function, the discriminator uses a model trained on faces, a constant facial recognition, an alignment between the biometric characteristics of the victim and those of the image it aims to achieve. The recognition model is essential in creating convincing deepfakes.

If we could impose strict limits, like the Parliament suggest and as well our demands , on these technologies, we might also control and perhaps limit the unregulated spread of deepfakes and the potential abuses associated with them.

In a world where uniqueness can be easily manipulated and replicated, it is our duty to protect what makes us truly unique. The issue is intricate and profound, but it is essential to tackle it with awareness and proactivity to ensure a future where technology amplifies the truth rather than distorting it.

The Worst-Case Scenario: A Future with Unrestricted Facial Biometrics

In an era where technology is advancing rapidly, facial biometrics represents one of the most discussed and potentially dangerous areas. These systems, unlike other models such as linguistic ones, are trained on faces – identifying and permanent biometric data. This makes them particularly powerful and intimate. The risk, therefore, is not just technical, but deeply human. Any biases present can lead to incorrect decisions, often with discriminatory implications, and the reflection on the ethics of their production should be at the heart of the discussion.

Imagine a world where biometric technology is not regulated: Profiling systems could potentially scan social network photos, assigning trustworthiness ratings based on obscure parameters. Cameras could record and analyze people’s behaviors, creating detailed behavioral profiles. In such a scenario, those holding this information would have disproportionate power, understanding individuals’ lives beyond any other tool or individual.

In this scenario of deregulation, the market for applications and hardware with biometric capabilities would explode, becoming commonplace. However, while the technology would be accessible to everyone, the real power – the ability to analyze and use these data – would be concentrated in the hands of a few large organizations

Paradoxically, to protect their privacy, people might resort to producing deepfakes of themselves. By creating false versions of themselves, they could attempt to blur and deceive profiling systems. But in such a dystopian world, are we really ready to renounce our true image to protect our privacy?

An extreme but perhaps effective solution would be to pollute the Internet with deepfakes of ourselves, so that our profile is associated with behaviors that are not typically ours, thus reducing the credibility of these surveillance providers and anonymizing our actual interests and identities.

Check the

infographic

.

Lastly, considering that the production of false images (deepfakes) is already prohibited, but in the case these models and applications became so widespread, their pervasiveness would make it nearly impossible to prosecute abuses.

Trust in technological media would decrease (even more), and authorities might focus only on the most flagrant cases, leaving the vast majority of offenders unpunished and consolidating a culture of distrust.

Concluding, the future of facial biometrics is a minefield of technical, ethical, and social challenges. It is our collective duty to deeply reflect on these issues and adopt appropriate measures to ensure a future where technology serves humanity, not against it.

Because this connection is complex, the time is running out, we play with deepfake of policymakers in the European Council , and you can help:

How Does This Connect to the (unregulation of) Foundation Models?

In the last phases of the Trilogue, as explained by Connor Dunlop in Regulating AI foundation models is crucial for innovation , Germany, France and Italy are pushing for Zero Regulation on Foundation Models. Quote:

Given the range and severity of risks that foundation models raise, these proposals are reasonable steps for ensuring public safety and trust – and for ensuring that the SMEs using these products can be confident they are safe.

But last week, France, Germany and Italy rejected these requirements and proposed that foundation models should be exempt from any regulatory obligations.

This position has now raised the prospect of indefinitely delaying the entire EU AI Act – which covers all kinds of AI systems, from biometrics technologies to systems that impact our electoral processes.

France and Germany claim these regulatory obligations will be too burdensome for a handful of companies that have raised hundreds of millions in funding to build open-source foundation models.

Even in the Executive Order of Biden ( our blogpost ), one certainty we can expect is the supervision of the Department of Commerce over the production of models, and this could ensure that the models produced and used in apps and services in the European market do not allow for the processing of biometric data.

So let’s use this measure to our advantage as Europeans, knowing that such marked and “certified” datapoints can be identified. Let’s enforce transparency on the models adopted, and ban the use of products based on models trained on biometric data.

As a conclusion, this infographic by EDRI, updates on the status of Our Requests :

💡 API

To better remind that once your Biometric data gets into the surveillance capitalist internet, personal data flow uncontrolled, we setup a method to:

pick the deepfakes pictures and biometric information, in JSON, via API:

https://dontspy.eu/api/individuals/%7B%22isfake%22:true%7D

You’re invited to submit more !

🤔 Discriminator

This was has been mentioned above as part of the AI workflow to produce deepfake, as detail, you should consider two components works together:

- The Generator: This component generates new data instances (like images or videos in the case of deepfakes). It tries to produce data that is indistinguishable from real, authentic data.

- The Discriminator: This component evaluates the data produced by the generator and determines whether it is real (authentic) or fake (generated). The discriminator learns to make this distinction by analyzing both real and fake data.

In the process of training a GAN, the generator and discriminator essentially compete with each other. The generator aims to produce increasingly realistic data, while the discriminator becomes better at distinguishing between real and fake. This adversarial process eventually leads to the generation of very convincing deepfakes.

🤔 Google said what?

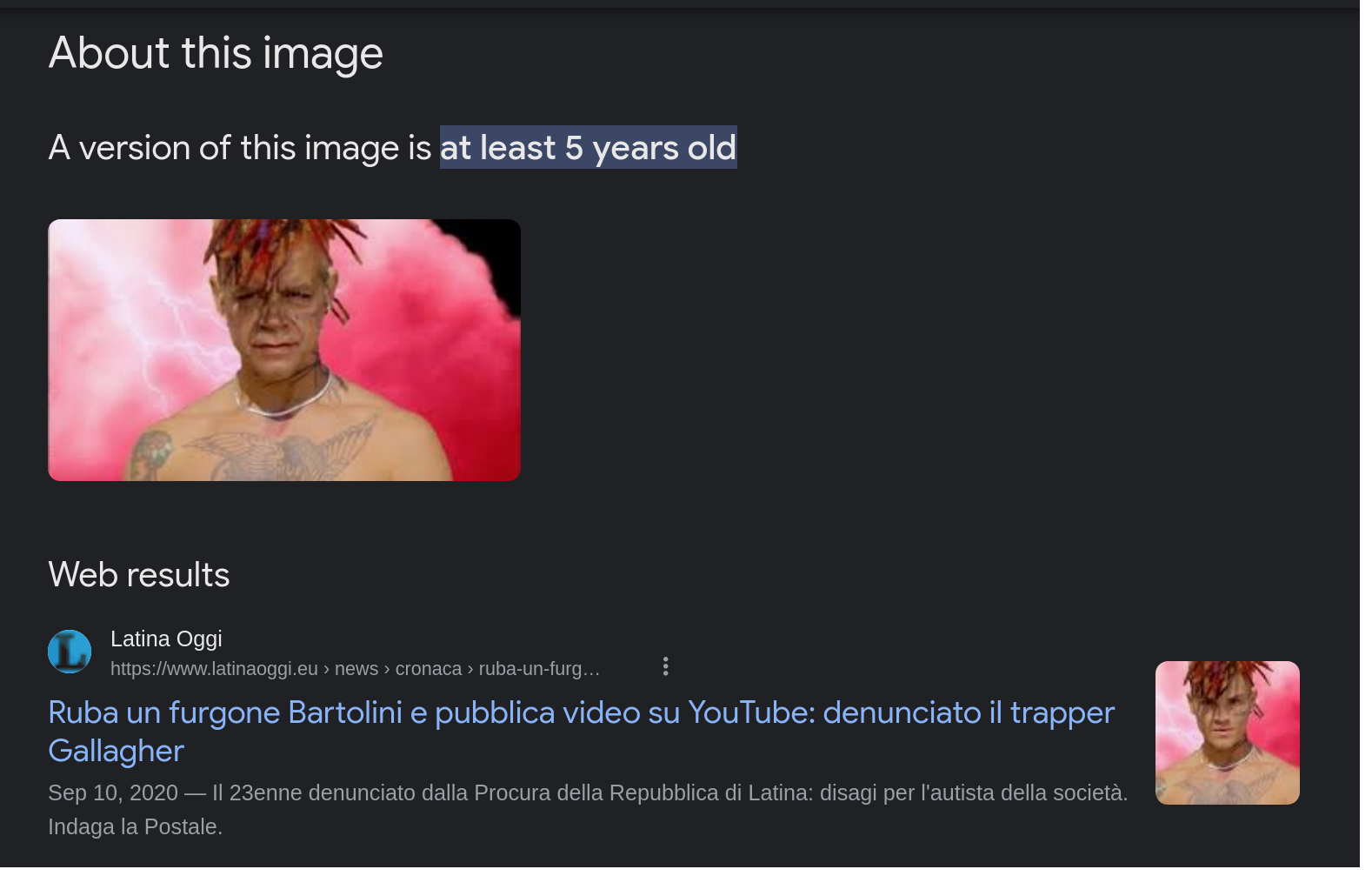

Google recently release some additional tool for “image trustworthyness” this is something that the press pick up as “this tool allows you to fight deepfake” but actually no. let’s see the large limit of this approach:

Screenshot from Google image ‘About this Image’ feature. It fully detect one of our fake, but because the picture was existing already

This do not happen with pictures that are fully AI generated or pictures that have never been published online before.